In addition to “commercially pure” titanium (often called “CP” or grade 2), there are two common alloys used in the bike industry; they are grade 5, (often called “six, four” because it’s 6% aluminum, 4% vanadium), and grade 9 (often called “three, two, five” because it’s 3% aluminum, 2.5% vanadium). The use of each material on a frame generally corresponds with their specific properties, or characteristics.

Grade 9 was originally produced for hydraulic systems in the aerospace industry in large part because of the ability to maintain its mechanical properties within a large temperature range (e.g. -300°F to 1000°F). It’s the most commonly used titanium alloy in the bike industry for other reasons; it’s stronger than CP, can be cold worked with high strength, exhibits good ductility, and can be machined and welded. As far as metals are concerned, one would be hard-pressed to find a better bicycle frame alloy when all characteristics are considered.

Although grade 5 is more common in other industries, particularly in aerospace, it has a solid home in the bicycle industry as well. It exhibits a higher strength than grade 9, but doesn’t form (e.g. seamless bicycle tubing) as easily or economically. Grade 5 titanium can be used as an expensive bicycle tube set, but it’s more commonly found as dropouts, brake mounts, fasteners, and yokes. The 6/4 titanium is also commonly used as weld wire but in the ELI form, which is defined as another grade of titanium; grade 23. ELI stands for Extra Low Interstitials, which means it’s a purer form of the grade 5, 6/4 titanium, particularly in regards to lower carbon and oxygen content. This makes a great weld wire due to its excellent fracture toughness and fatigue strength.

The 6/4 titanium is also commonly used as weld wire but in the ELI form, which is defined as another grade of titanium; grade 23. ELI stands for Extra Low Interstitials, which means it’s a purer form of the grade 5, 6/4 titanium, particularly in regards to lower carbon and oxygen content. This makes a great weld wire due to its excellent fracture toughness and fatigue strength.

Grade 2 titanium is primarily used in applications having less strength requirements. Small pieces like housing saddles and stops, water bottle eyelets, fender and rack mount eyelets, etc. are generally CP. Grade 2 titanium exhibits the same excellent corrosion resistant qualities as the other Ti alloys but is less expensive and more cost effective to machine. Using grade 2 titanium in this application minimizes costs without affecting performance.

Grade 2 titanium is primarily used in applications having less strength requirements. Small pieces like housing saddles and stops, water bottle eyelets, fender and rack mount eyelets, etc. are generally CP. Grade 2 titanium exhibits the same excellent corrosion resistant qualities as the other Ti alloys but is less expensive and more cost effective to machine. Using grade 2 titanium in this application minimizes costs without affecting performance.

Regardless of the alloy used, titanium in general, exhibits the highest strength to weight ratio of any metal alloy (not including high-entropy alloys). This is a key aspect in why titanium is so advantageous. The strength-to-weight ratio determines how much of a given material is required for a specific purpose. In general, the higher the strength-to-weight ratio of a given material, the less material is required for a given function. This isn’t as explicit as it may sound; often the stiffness of the bicycle design will dictate the amount of material used since stiffness is mostly influenced by tube diameter.

Titanium is often erroneously considered a rare metal; likely because of its high cost. It is the ninth most abundant element in the Earth’s crust (0.62% of the Earth’s crust is titanium), and the fourth most abundant structural element, so it is not rare. It is relatively expensive, however, due to the extraction process as well as its difficulty to machine and manipulate.

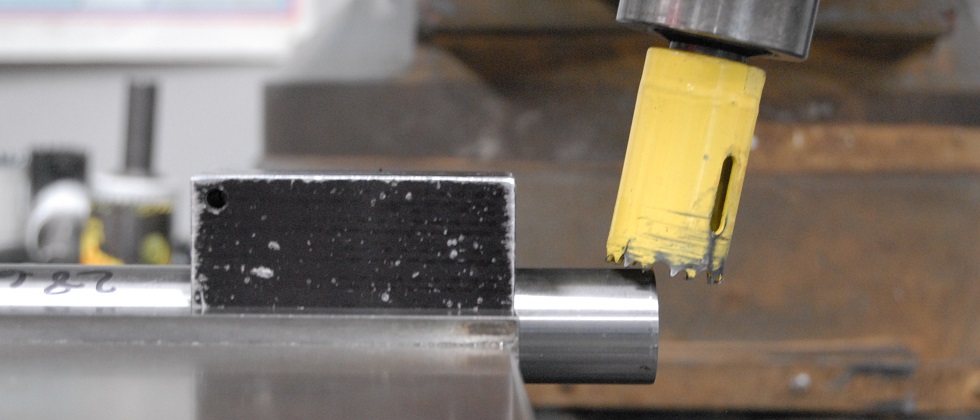

In comparison to steel, titanium is 15x more expensive to extract from ore, 20x more expensive to refine, 30x more expensive to form ingots, and 50-83x more expensive to form sheets! Compared to aluminum, titanium is 3x more expensive to extract from ore, 2.9x more expensive to refine, 6.4x more expensive to form ingots, and 10-15x more expensive to form sheets. Titanium requires additional purging when welding, and will wear down cutting tools significantly quicker than steel or aluminum. All this is to show that titanium is truly as expensive as advertised.

Titanium Frames

The good news is, once the frame is built, assuming it was fabricated correctly, the frame will likely outlive the rider. Titanium has better fatigue resistance than steel and does not corrode in our environment. An example to highlight titanium’s fatigue resistance is to examine a stainless steel spoke: every revolution of a wheel, a spoke goes through a stress cycle (increasing and decreasing tensions); stress cycles lead to fatigue. The Race Across America (RAAM) spans 3000 miles, and a stainless steel spoke has little issue making this trek, resulting in approximately 2,266,681 wheel revolutions. That’s over 2.2 million stress cycles per each spoke. And titanium has an even greater fatigue life!

There are plenty of painted titanium frames, but due to the corrosion resistance, but they don’t need to be coated for protection. A raw titanium frame will last as long as a painted or powder-coated frame (all things considered equal). Titanium does not react with salt solutions, temperature, or moisture cycles. Many titanium frame manufacturers simply brush the titanium with a scotch bright pad and follow with a wax to make it shine.

There are plenty of painted titanium frames, but due to the corrosion resistance, but they don’t need to be coated for protection. A raw titanium frame will last as long as a painted or powder-coated frame (all things considered equal). Titanium does not react with salt solutions, temperature, or moisture cycles. Many titanium frame manufacturers simply brush the titanium with a scotch bright pad and follow with a wax to make it shine.

The Jist?

The four most common frame materials (steel, aluminum, titanium, and carbon composite), all have advantages and disadvantages in regards to bicycle frame construction. If longevity and ride quality are primary considerations, and the frame design is without rear suspension, (e.g. gravel bike, cyclocross bike, road bike, commuter, hard tail mountain bike, etc.), titanium is arguably the best choice.

Why is titanium not the best choice for full suspension frames? That’s an article for another time.